Memories of Fallen cities

Istanbul

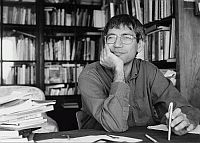

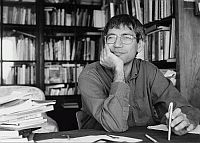

Orhan Pamuk (translated from Turkish by Maureen Freely)

When Orhan Pamuk, Turkey’s leading author spoke with the Swiss paper Tages-Anzeiger,in February last year, of the Turkish genocide of the Armenians, the Turkish govt promptly brought criminal charges against him for anti-nationalism.

As Pamuk says here :

“it was taboo to discuss these matters in my country. Among the world’s serious historians, it is common knowledge that a large number of Ottoman Armenians were deported, allegedly for siding against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, and many of them were slaughtered along the way. Turkey’s spokesmen, most of whom are diplomats, continue to maintain that the death toll was much lower, that the slaughter does not count as genocide because it was not systematic, and that in the course of the war Armenians killed many Muslims, too."

Government condemnation was not all. In the Turkish province of Sitculur, the governor ordered that Pamuk’s books be destroyed: it was Pamuk’s movie star like popularity and status that prevented book bonfires.

Says Pamuk of the Turkish govt’s stance

The hardest thing was to explain why a country officially committed to entry in the European Union would wish to imprison an author whose books were well known in Europe, and why it felt compelled to play out this drama (as Conrad might have said) “under Western eyes.” This paradox cannot be explained away as simple ignorance, jealousy, or intolerance, and it is not the only paradox. What am I to make of a country that insists that the Turks, unlike their Western neighbors, are a compassionate people, incapable of genocide, while nationalist political groups are pelting me with death threats? What is the logic behind a state that complains that its enemies spread false reports about the Ottoman legacy all over the globe while it prosecutes and imprisons one writer after another, thus propagating the image of the Terrible Turk worldwide? When I think of the professor whom the state asked to give his ideas on Turkey’s minorities, and who, having produced a report that failed to please, was prosecuted, or the news that between the time I began this essay and embarked on the sentence you are now reading five more writers and journalists were charged under Article 301, I imagine that Flaubert and Nerval, the two godfathers of Orientalism, would call these incidents bizarreries, and rightly so.

Istanbul, Orhan Pamuk’s latest offering is part autobiography and part biography of the city. The city runs through Pamuk’s veins and except for a brief stint in New York, Pamuk has always been there. As he says, his literature comes from never having left.

Conrad, Nabokov, Naipaul-these are writers known for having managed to migrate between languages, cultures, countries, continents, and even civilizations.

But great literature can also come out of never having gone away: indeed having stayed on in the same city and same home.

Here we come to the heart of the matter: I’ve never left Istanbul, never left the houses, streets, and neighborhoods of my childhood. Although I’ve lived in different districts from time to time, fifty years on I find myself back in the Pamuk Apartments, where my first photographs were taken and where my mother first held me in her arms to show me the world.

We live in an age defined by mass migration and creative immigrants, so I am sometimes hard pressed to explain why I’ve stayed, not only in the same place but the same building. My mother’s sorrowful voice comes back to me: Why don’t you go outside for a while? Why don’t you try a change of scene, do some traveling…?

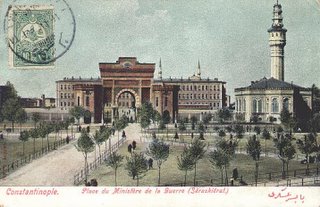

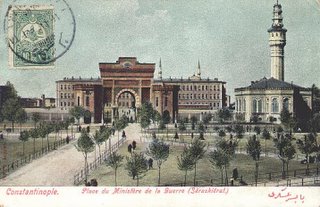

But Istanbul is also the city where Pamuk experiences hüzün; the turkish word for melancholy. Hüzün is the feeling of sadness, nostalgia and defeat at the thought of the bygone era and lost glory. Traces of ruins of the Ottoman rule (as Pamuk is wont to call it-instead of empire) are everywhere, as is the pervading sense of melancholy. So that today’s Istanbulu feels more at ease using grocery stores and coffee houses as landmarks instead of old structures in ruin.

This quiet grief and mourning for a city’s past was reminiscent of the lamentations of a poet and monarch of Delhi. Exiled by the British to Rangoon in Burma, Bahadur Shah Zafar had said of the defeated and vanquished Delhi:

subah ro ro ke shaam hotee hai shab tadap kar tamaam hoti hai (The morning painfully gives way to sunset, and then there is only grief)

Sad and beautiful as Pamuk's narration is, intertwining his own life with that of the city, the black and white photographs further fuel the feeling of grief. In other words, more hüzün.

Istanbul

Orhan Pamuk (translated from Turkish by Maureen Freely)

When Orhan Pamuk, Turkey’s leading author spoke with the Swiss paper Tages-Anzeiger,in February last year, of the Turkish genocide of the Armenians, the Turkish govt promptly brought criminal charges against him for anti-nationalism.

As Pamuk says here :

“it was taboo to discuss these matters in my country. Among the world’s serious historians, it is common knowledge that a large number of Ottoman Armenians were deported, allegedly for siding against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, and many of them were slaughtered along the way. Turkey’s spokesmen, most of whom are diplomats, continue to maintain that the death toll was much lower, that the slaughter does not count as genocide because it was not systematic, and that in the course of the war Armenians killed many Muslims, too."

Government condemnation was not all. In the Turkish province of Sitculur, the governor ordered that Pamuk’s books be destroyed: it was Pamuk’s movie star like popularity and status that prevented book bonfires.

Says Pamuk of the Turkish govt’s stance

The hardest thing was to explain why a country officially committed to entry in the European Union would wish to imprison an author whose books were well known in Europe, and why it felt compelled to play out this drama (as Conrad might have said) “under Western eyes.” This paradox cannot be explained away as simple ignorance, jealousy, or intolerance, and it is not the only paradox. What am I to make of a country that insists that the Turks, unlike their Western neighbors, are a compassionate people, incapable of genocide, while nationalist political groups are pelting me with death threats? What is the logic behind a state that complains that its enemies spread false reports about the Ottoman legacy all over the globe while it prosecutes and imprisons one writer after another, thus propagating the image of the Terrible Turk worldwide? When I think of the professor whom the state asked to give his ideas on Turkey’s minorities, and who, having produced a report that failed to please, was prosecuted, or the news that between the time I began this essay and embarked on the sentence you are now reading five more writers and journalists were charged under Article 301, I imagine that Flaubert and Nerval, the two godfathers of Orientalism, would call these incidents bizarreries, and rightly so.

Istanbul, Orhan Pamuk’s latest offering is part autobiography and part biography of the city. The city runs through Pamuk’s veins and except for a brief stint in New York, Pamuk has always been there. As he says, his literature comes from never having left.

Conrad, Nabokov, Naipaul-these are writers known for having managed to migrate between languages, cultures, countries, continents, and even civilizations.

But great literature can also come out of never having gone away: indeed having stayed on in the same city and same home.

Here we come to the heart of the matter: I’ve never left Istanbul, never left the houses, streets, and neighborhoods of my childhood. Although I’ve lived in different districts from time to time, fifty years on I find myself back in the Pamuk Apartments, where my first photographs were taken and where my mother first held me in her arms to show me the world.

We live in an age defined by mass migration and creative immigrants, so I am sometimes hard pressed to explain why I’ve stayed, not only in the same place but the same building. My mother’s sorrowful voice comes back to me: Why don’t you go outside for a while? Why don’t you try a change of scene, do some traveling…?

But Istanbul is also the city where Pamuk experiences hüzün; the turkish word for melancholy. Hüzün is the feeling of sadness, nostalgia and defeat at the thought of the bygone era and lost glory. Traces of ruins of the Ottoman rule (as Pamuk is wont to call it-instead of empire) are everywhere, as is the pervading sense of melancholy. So that today’s Istanbulu feels more at ease using grocery stores and coffee houses as landmarks instead of old structures in ruin.

This quiet grief and mourning for a city’s past was reminiscent of the lamentations of a poet and monarch of Delhi. Exiled by the British to Rangoon in Burma, Bahadur Shah Zafar had said of the defeated and vanquished Delhi:

subah ro ro ke shaam hotee hai shab tadap kar tamaam hoti hai (The morning painfully gives way to sunset, and then there is only grief)

Sad and beautiful as Pamuk's narration is, intertwining his own life with that of the city, the black and white photographs further fuel the feeling of grief. In other words, more hüzün.